- Centre for Holocaust Education

- Research

- Use our research to inform your teaching

Use our research to inform your teaching

We are uniquely responsive to the challenges identified in the national studies we carried out with students and teachers. Seven research briefings have been developed to help teachers use research to inform their classroom practice and increase the effectiveness of teaching and learning about the Holocaust.

-

Non-Jewish Victims of Nazi persecution and murder

Download briefing

The overwhelming majority of students recognised Jews as victims of the Holocaust.

Counter to accepted definitions, with age, students also mentioned gay men, disabled people and the Roma and Sinti as victims of the Holocaust.

Furthermore, students were largely unfamiliar with the unique experiences of each of these different groups, the particular policies enacted against them and the specific reasons for their persecution.

The UCL Centre for Holocaust Education uses the term ‘the Holocaust’ to specifically denote the genocide of European Jews. In addition to the genocide of European Jews, the Nazis and their collaborators committed mass violence and murder against many groups of people. All victims of Nazi persecution and murder deserve full recognition in their own right, rather than to be simply listed under the heading ‘Holocaust’.

Greater differentiation is needed, not in order to create any hierarchy of suffering but to genuinely understand why and how individual people came to be persecuted and killed.

‘What happened to the Jews of Europe? The Holocaust and the persecution of other victim groups’ is designed to provide both depth and overview of the history of the Holocaust and reveals how the persecution and murder of the Jews was interwoven with and related to Nazi crimes against other victim groups, including political opponents, the disabled, Roma and Sinti, gay men, Poles, Soviet POWs, and Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Crucially, it ensures that the distinctiveness of each is understood and appreciated.

-

Victims of the Holocaust

Download briefing

Most students indicated that there was something distinctive about the persecution of the Jews but were unable to explain what this distinctiveness was.

Many did not see the Nazi intent to murder all Jews everywhere they could reach them as a defining feature of this genocide. Furthermore, there was considerable uncertainty and imprecision in students’ understanding of the policies enacted against Jews.

Students were not able to provide robust answers to the question of why Jews were targeted. With 68% unaware of what ‘antisemitism’ meant, their explanations tended to rest on common stereotypes and misconceptions about Jewish people, rather than on the prejudices of those who persecuted them.

Many public commemorations, historical representations and educational initiatives of the Holocaust give prominence to the fate of the Jews. Regrettably, often this is mistakenly taken as evidence that Jews ‘dominate the media’, or ‘use’ the Holocaust to further their own interests at the expense of others. This can play into age-old antisemitic myths of Jewish influence and power. If young people are not to be drawn into such misunderstandings, then it is crucial that they know what was specific about the genocide of the Jews in order to understand why it is given so much attention.

Students need to learn about Nazi beliefs, ideology and policies to explain why Jews were targeted without looking to some ‘fault’ within the victims themselves, or attempting to rationalise their persecution.

They need to understand this in the context of a long history of European anti-Judaism, and to examine broader reasons for why and how many people throughout Europe became complicit in the crimes perpetrated against their Jewish neighbours.

‘What happened to the Jews of Europe? The Holocaust and the persecution of other victim groups’ explores the distinctiveness of different Nazi crimes perpetrated against a range of victim groups.

‘Who were the six million? Exploring Jewish life before the Holocaust’ reveals the vibrancy and diversity of pre-war Jewish life and helps students to appreciate the magnitude of what was lost in the Holocaust.

‘Striving to live: how did Jewish people respond and resist during the Holocaust?’ engages students with the astonishing range of responses by Jewish people to the unfolding genocide.

‘Nazi antisemitism: Where did it come from?’ locates and contextualises Nazi racial thinking in terms of the long history of European anti-Judaism.

‘Being Human? Choices, behaviours and the Holocaust’ extends the responsibility and complicity for the genocide beyond Hitler and the Nazi hierarchy to ordinary people in Germany and across the continent. Taken together, these teaching and learning activities can lead students to powerful explanations of ‘Why the Jews?’

-

An unfolding genocide

Download briefing

Typically, students in Years 7 to 11 did not have a secure or confident understanding of the chronology of the Holocaust. 40.2% of students incorrectly believed that the ‘organised mass killing of Jews’ began in 1933, immediately when Hitler came to power.

Many were unable to detail specific policies or events that dramatically impacted on the lives of Jews (e.g. the April 1933 Boycott, the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, or Kristallnacht in 1938).

Very few appeared to fully grasp the significance of the relationship between the Second World War and the Holocaust.

If students are to understand that genocides do not happen merely because someone wills it, then they need to move beyond the idea that Hitler just decided to kill the Jews (and others) when he came to power, and that this was blindly carried out.

Instead, it is important to see how the development from persecution to genocide unfolded and evolved over time; that key decisions were taken by a range of individuals and agencies; and that the context of a European war was critical in shaping these decisions.

‘What happened to the Jews of Europe? The Holocaust and the persecution of other victim groups’ provides a powerful historical overview of the chronological development of the Holocaust (as well as that of the persecution and murder of non-Jewish victims). It engages students in the events and development of the persecution and mass murder, enabling them to identify key phases and turning points and building powerful knowledge of this complex past.

-

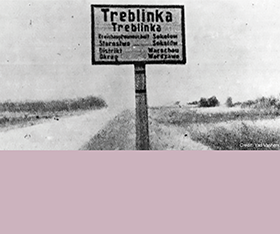

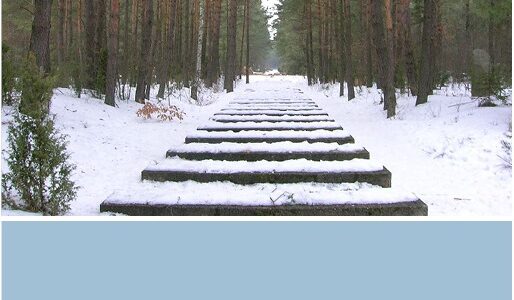

Spaces of killing

Download briefing

Students typically had a German-centric view of the Holocaust, wrongly believing that most of the killing took place within German borders, and few recognising the continent-wide scale of the genocide.

Students commonly referred to camps and ghettos but many had limited understanding of where they were established or for what purpose. Students often confused concentration camps (where very large numbers of people from many victim groups were persecuted and many were killed) with death camps (specifically designed for the mass murder of Jews, within hours of their arrival).

The majority of students did not know about the Einsatzgruppen (Nazi killing squads) and the mass shootings of up to two million people in the East.

Knowledge of the ‘spaces of killing’ is crucial to an understanding of the Holocaust. If students do not appreciate the scale of the killings in the East, then it is impossible to grasp the devastation of Jewish communities in Europe or the significance of the genocide in destroying ways of lives and vibrant cultures that developed over centuries.

Knowledge of the different spaces (the concentration camps; the ghettos; the killing fields of the Einsatzgruppen; the death camps), why they were created and their differing roles, can lead to far deeper understanding of the particular histories of different victim groups.

The historical overview and timeline in our CPD workshop and educational resource, ‘What happened to the Jews of Europe? The Holocaust and the persecution of other victim groups’ can be used to highlight the development of the concentration camp system, the Euthanasia killing sites, the establishment of the ghettos, the actions of the Einsatzgruppen, and the development of the death camps. In each case, the histories of a range of victims and how they relate to these spaces can be examined.

Furthermore, it is possible to go into more depth on aspects of the sites of killing through a range of twilight CPD programmes: ‘A space called Treblinka’ looks at the chaotic development of the process of mass murder in the death camps; ‘Forgotten History: What happened in the East and how do we know?’ (coming soon) explores the mass shootings by the Einsatzgruppen and their collaborators.

-

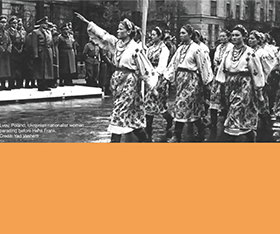

Agency and responsibility

Download briefing

When asked who was responsible for the Holocaust, 81.9% of all students surveyed ascribed responsibility only to Hitler and/or ‘the Nazis’. However, students’ knowledge and understanding of ‘the Nazis’ was limited.

Very few students identified the widespread perpetration, collaboration or complicity of the German and non-German people across Europe in countries allied to or occupied by Nazi Germany.

Most students believed that the German people supported Hitler and his actions because they were ‘brainwashed’, ‘scared’ or they ‘did not know’ about the Holocaust.

If students only see Hitler and a few leading Nazis as responsible for the Holocaust, then the major challenge of understanding how and why people across Europe became complicit in the murder of their neighbours is overlooked.

This has significant consequence for understanding how and why the Holocaust happened: explanations that rest on the actions of a powerful individual and the fanatics that surrounded him fail to recognise the extent to which the genocide had origins deep within broader European social, cultural and political traditions.

‘Being Human? Choices, behaviours and the Holocaust’ is specifically designed to address common myths and misconceptions about not only perpetrators and collaborators, but also bystanders and rescuers. It helps teachers to uncover students’ preconceptions about who these people were, tending to reveal a range of stereotypes and misconceptions, such as ‘mad and evil’ perpetrators or myths such as ordinary people were brainwashed, or didn’t know what was happening.

By using the resources provided by the UCL Centre for Holocaust Education teachers can invite students to test these ideas against a range of engaging and thought-provoking case studies and discover that the past is far more complex, nuanced, and troubling than they had imagined. In so doing, they come to understand that responsibility for the Holocaust extended far wider than simply ‘Hitler and the Nazis’. They are then left with searching questions about what it is to be a citizen in the modern world.

-

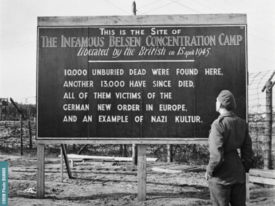

Britain and the Holocaust

Download briefing

Survey responses suggested that students of all ages had a limited and often erroneous understanding of the British government’s response to the Holocaust.

When asked ‘what happened when the British government knew about the mass murder of the Jews?’ 34.4% of students wrongly suggested that Britain declared war on Germany, and 23.8% incorrectly believed that Britain did not know anything until the end of the war. Only 6.7% chose the most appropriate answer: that Britain said they would punish the killers when the war was over.

While it is certainly important for young people to know that Britain was one of the Allied Powers that eventually defeated Nazi Germany, and that this did indeed bring an end to the Nazi crimes, it would be a distortion of that past to believe that Britain fought the Nazis in order to save the Jews. Such an idea is not only harmful to students’ knowledge of the Holocaust, but also to their understanding of why Britain went to war.

Deeper historical understanding of how much Britain actually knew about the genocide and how the government and the public responded when information about mass killings of Jews became available provides students the opportunity to understand how the history of the Holocaust links to, and is part of, their own history. It also allows them to grapple with significant ethical and political questions and to critically consider issues of national and international responsibility.

‘What were British responses to the Holocaust?’ draws upon rich archival material to facilitate students’ detailed enquiry into what the British government and public knew and when; how this knowledge was comprehended; and the attitudes and response that followed.

In the light of this more complex knowledge of Britain’s role during the Holocaust, teachers and students may wish to reflect on how this country should respond to other unfolding genocides and refugee issues in the world today.

-

Explaining the Holocaust

Download briefing

Where students attempted to identify causes of the Holocaust, they overwhelmingly did so with central reference to Hitler and/or ‘the Nazis’.

Most students appeared to have very limited understanding of how or why so many other people across the continent also became complicit in the persecution of the Jews and commonly relied upon notions of ‘brainwashing’, fear and/or ignorance in their attempts to explain this.

Students were concerned with why the Jews were specifically targeted, but had considerable difficulty in providing answers to this question. With 68% of survey respondents not recognising the term ‘antisemitism’, many students appeared to resort to stereotypical misconceptions regarding who ‘the Jews’ were to explain why they were targeted.

The majority of students appeared to have limited understanding of the ideological, cultural, political and economic conditions which made the Holocaust possible.

If students locate responsibility for the Holocaust only in the personal beliefs and prejudices of Hitler and the Nazis, then they overlook both the complicity of many thousands of others across the European continent, and the deep ideological, cultural and political roots of the Holocaust. Recognition of this context means that the Holocaust can then not be simply ‘explained away’ as an aberration of the Nazi era, but must be seen as a part of the wider western tradition, which has profound implications for the meanings students may draw from this history.

Developing the skills and understanding to explain why events have happened in history is a fundamental component of historical thinking. It encourages learners to move beyond the possession of discrete items of knowledge and the capacity to simply describe something from the past, towards being able to comprehend the inter-relationships between different forces and their various roles in bringing that something about. This is important not only in understanding the Holocaust, but, crucially, in helping students become informed and critical members of society.

The twilight CPD and accompanying classroom materials in ‘Nazi antisemitism: Where did it come from?’ uncover the origins of this ‘longest hatred’, and explore continuity and change from medieval anti-Judaism to modern antisemitism. They provide essential knowledge and understanding to counter common myths and stereotypes of the Jewish people.

The interactive timeline ‘What happened to the Jews of Europe? The Holocaust and the persecution of other victim groups’ places key events and decisions in their historical context, making clear the connections between the radicalisation of Nazi policy and the outbreak and course of the Second World War. It also highlights the dynamic between actions ‘from above’ (the decisions of Hitler and the Nazi leadership) and that of initiatives ‘from below’ (how lower level functionaries and the general public both responded to and – at times – drove forward the unfolding persecution).

The powerful case studies in ‘Being Human? Choices, behaviours and the Holocaust’ develop this further, through case studies that focus both on the ideology of Hitler, Himmler and Heydrich as well as the wide range of motivations of other individuals and agencies that became complicit in the genocide.

Download student research report

What do young people know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools (2016)

Download teacher research report

Teaching about the Holocaust in English secondary schools: An empirical study of national trends, perspectives and practice (2009)