Questions and questioning are defining features of teaching and learning. The processes of asking and answering questions are the central dynamos of a classroom – organising and managing behaviours, driving activities, and enabling the construction of new knowledge and understanding. We all know that questioning is important. And, we all know that on certain occasions, judgements about our teaching practice will take into consideration the questions we ask and our approach to questioning. But when teaching and learning is taking place remotely, what are the implications for this critical activity?

By: Dr Andy Pearce and Nicola Wetherall MBE

Asking questions

As with many issues in education, it is often worth returning to the matter of rationale. Since questioning can serve any number of purposes, establishing why we are asking a question is inseparable from the context in which it is being asked and the objective(s) it is directed towards achieving. Recognising these considerations and having clarity about them are fundamental to the construction of sound questions. But questioning is not a mechanical, mechanistic operation: particularly in an educational setting, where the respondent to a question is a human being, not an automaton. And especially when the subject matter the learner is engaging with is shrouded in grayscale, rather than shaded in black and white.

Principles of questioning

These considerations lie behind our intrigue as to what makes a ‘good’ question. That this can be answered in multiple ways tells us all we need to know: there is no universal template, even if we all find ourselves at one moment or another uttering the words ‘that’s a good question!’ This does not mean, however, that there aren’t some common principles which we might apply in our approaches to questioning. Evidently questions need to be intelligible – learners need to be clear what they are being asked; questions also need, where appropriate, to be aware of their specificities – there is a difference, for instance, between asking ‘why’ and asking ‘how’; questions should be authentic – they should reflect a concern that the teacher themselves has; and questions need to be cognisant of their potential range of answers – even where the answer is not ‘known’ or definitive. This latter factor raises two further points: firstly, that it is possible to provide a response to a question, but there is a difference between a response and an answer; secondly, that not all answers are equally valid, legitimate, or factually accurate. This has a direct consequence for pedagogy, for it highlights how sometimes an answer requires further questions, in order to either tease out underlying thinking, or to help someone recalibrate a route around their misunderstandings.

Questioning and Holocaust pedagogy

Questioning, amongst other things, is an evaluative action. As a tool for assessment, questioning has a crucial role to play in determining learner’s knowledge and understanding. With this in mind it is interesting that the Centre’s 2009 research into teaching practices found a reticence among some teachers towards formally assessing students’ learning. In the decade since, anecdotal evidence suggests there may be a wider uncertainty among teachers as to how to approach assessment and progress.

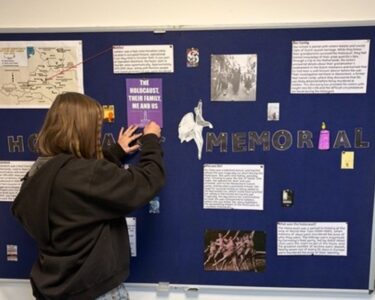

Is there a connection between teachers’ uncertainties towards assessment, when it comes to the Holocaust, and broader issues around questioning? For over a decade, the signature feature of the Centre’s pedagogy has been guided questioning: a strategy that foregrounds students’ construction of knowledge, with a view to enabling them to develop the capacity to ask their own questions. It is an approach which takes centre-stage in our ‘Ordinary Things?’ and ‘Authentic encounters’ material, but can also be found in other resources such as ‘A space called “Treblinka”’ and ‘Telling the story of resistance’. Through this technique we have found that teachers are able to help students to not simply develop their ‘substantive’ or ‘content’ knowledge of the Holocaust, but to simultaneously enhance their understanding of both the history and the fundamental challenges it poses us.

Questioning remotely

Much of the above speaks to in-person, mediated questioning by a skilful practitioner – what principles or frameworks could be used when directing home or remote learning?

One approach that would encourage young people to think about a range of questioning and what it is that makes a ‘good question’ in a particular context, could be the use of question grids. Variants of these scaffolds exist, but essentially they take the form of a table which lists the who, what, when, where, why, which and how, against the ‘is (present), did (past), can (possibility), could/could (probability), will (prediction) and might (imagination)’ to frame a series of questions. Such approaches can be used in a classroom in response to topic, image, artefact or other stimulus, but they can also be used to support students in remote learning.

‘A note from Leon’

Let’s take a concrete example. Within our open access materials is ‘Holocaust: In the House of a Survivor’, a short film, which sits within a suite of sources entitled ‘A Note from Leon’. The film features the Centre’s Ruth-Anne Lenga in the home of the Holocaust survivor, Leon Greenman; it a personal and intimate film, deceptive in its simplicity, for within it lies deep learning and powerful questioning opportunities. The film, together with a range of resources aims to stimulate reflection on the human impact and long-term effects of the Holocaust and engage young people in consideration of what stories lie behind material traces of the past. The materials and the approach underpinning it, seek to build knowledge and understanding, the cognitive, but also support SMSC, emotional literacy and works at a very human, holistic level.

When delivered in a classroom setting and supplemented by other open access materials on the ‘legacy’ of the Holocaust, a teacher can use questioning to effectively explore nuance, clarify misconceptions, and deepen student understanding about the long-term impact of the Holocaust on an individual. In a remote learning environment, of course, such immediate engagement and pedagogical interaction is missing. So how might this absence be addressed and overcome? How can we support students develop their thinking?

It is worth remembering that the film, in effect, presents two stories. The first is that of the note and the objects found in the lozenge box: a self-contained story, of someone discovering something left behind, and encountering the reflections of the person who once owned the objects. A moving and touching tale in and of itself, the story acquires greater depth and potency by the narrative which overarches it: namely, the history of these rings and the tragic fate of Else and Barney. Humans, as we know, are fascinated by stories: storytelling has been a central feature of our evolution, and are a key part of children’s development. Importantly, stories can transcend the dislocation that can come from remote teaching and learning.

Because ‘A note from Leon’ functions as a exercise in storytelling, we can be confident that if we ask students to watch the film they are likely to be left asking questions – even if they are unfamiliar with Leon’s story, or lack detailed knowledge of the Holocaust. Moreover, if we help students to organise and articulate these questions, we can glean insights into their understanding from the questions they ask. Providing students with the question grid mentioned earlier can then encourage them to think about a variety of questions, types of questions. Once completed, the question grid can serve as the starting point for follow-up work. This begins by asking students which three questions they believe were the ‘best’, or were ‘good questions’, and to provide their reasons for these judgements.

Questioning as a vehicle to higher order thinking

Such an exercise would encourage students to consider the range of questions available and characteristics and usefulness of each type (whether closed, open, higher/lower order, hypothetical or hinge questions), whilst also laying the foundations for both teacher-student dialogue and peer-to-peer conversations. Students could also be directed to identify a number of questions for a research topic, with the teacher/school providing 2-3 recommended additional resources to help answer/address a limited number of them. The question grid thus becomes a framework to support young people both access the film and enter into the processes of sense and meaning-making. It is a framework which has wide application, and could be similarly used to explore a stimulus image, artefact, source document and so on.

Building upon this questioning scaffold, there are other ways young people can engage with powerful questioning. Students could take their original question grid responses and develop a graph or diagram. A horizontal axis could see students order or rank the questions they have generated along a ‘Interest Level’ continuum– that is to say, how likely is the question to inspire new thinking and new possibilities, and be simply indicative of the student’s interest level. A vertical axis could be added, almost graph like, and this could be flexibly utilised. A vertical axis could represent ‘Complexity‘ (from ‘closed factual questions’ to ‘open, conceptual questions’) – that is how far the question would deepen their understanding and generate complex thinking. Students could feedback their opinions, shaped by the teacher, to identify the best questions – which then could be the subject of further exploration. Having the questions very visible means you can also flexibly rearrange, such as selecting the ‘best’ nine questions and creating a new ‘diamond nine’ formation. As you can see, the possibilities are endless.

From theory to practice

The transition to remote teaching and learning thrust upon us by the coronavirus epidemic poses a raft of challenges – from the practical and the philosophical, to the technical and pedagogic. It is a shift which has direct consequences for the role of questioning in the educational process, and its execution. Much ink will (virtually) be spilt over these matters in the coming weeks. Indeed, in a recent TES article, it was suggested that asking a large number of questions was a key principle of remote teaching and learning. The reasoning for this has a logic. But because of the particularities of remote teaching and learning and the fundamental absence of the educator in the immediate physical vicinity of the learner, there is also an added premium placed on questioning: more than ever, questioning needs to be considered, its various pathways thought out and thought through, and the principles of ‘good’ questioning applied in practice.