‘As an 11-year-old I remember reading with amazement how a watchmaker’s family in Holland built a secret room in their attic to hide Jewish people during the Holocaust. I had no idea that 25 years later I would be in the middle of another man-made catastrophe. The gorgeous little country of Rwanda where we had made our home was imploding on itself as neighbours were actually killing neighbours.

The genocide against the Tutsi was 25 years ago and for the last 15 years I’ve been travelling to schools around the globe sharing stories, eye witness stories of both Rwanda falling apart, and Rwanda putting itself together again, rebuilding trust through restorative justice initiatives. At each school students ask, “Why? How could neighbours do that to each other?” And each time I tell them, genocide stems from thinking that say’s “MY world would be better WITHOUT “you” in it.” It’s the most extreme form of exclusive problem-solving that I know. Tragically today it’s still readily found in every country. At times it’s even found to some degree in my own heart, not that I want to kill anyone, it’s just there when I’m thinking it would be nice too not deal with certain people.

Today, more than ever, I believe that the man-made tragedy of genocide is preventable and that it starts with my own self-examination.

Let me tell you a story. Once upon a time, Thursday night, April 7th 1994, to be exact, a gang of Interahamwe, a killing squad, came to the gate of our home.

We had been bombarded by gunfire, shouts, and the bashing in of metal doors all day long, as our neighbours with Tutsi ID cards were being hunted and killed. As we put our three young children to bed in the hallway that Thursday night, effectively putting as many brick walls as we could between them and the bullets, we had no idea that our neighbour ladies were outside working to save our lives. When they heard a gang was gathering, they sprang into action. Courageously they worked their bodies through the crowd until they stood between the heavily armed group and our gate.

There had been wild rumours that the Belgians were one possible group who had shot the president’s plane down – the act that was used to launch the genocide. I don’t know it we were being confused for Belgians, or I really don’t know what these men whose minds were set on murder were thinking. But the neighbour ladies said that they were planning to kill our children, all of us. But it didn’t happen, because these ladies heroically stepped up, at great risk to themselves, and started telling stories. Stories of our family doing small acts of kindness over the 4 years we had lived in the neighbourhood. Stories of help with a funeral, of a pregnant mom driven to the hospital in the middle of the night, of our red-headed 5-year-old boy dodging in and out of neighbours’ homes playing games with his friends. Stories of ‘our kids playing with their kids’. They used these stories to change the thinking, feeling and action of those who came and meant us harm.

Before Teresa and I ever made the decision that I would stay in Rwanda to help, and she would take our kids to safety, our neighbour ladies were valiantly putting their lives on the line, telling stories and reframing our family in the minds and eyes of the killing squad that dark violent night.

Over the years I’ve struggled with the horrors I witnessed, as more than a million Tutsi and some courageous moderate Hutu were brutally slaughtered. Over the years I searched for a strategy to deal with the nightmares, the PTSD. And the practice of the strategy I found has radically changed every relationship I have. I believe it’s a strategy that can even prevent genocide.

This strategy is called reframing. Reframing situations, reframing the other, and at times reframing myself.

Reframing can shift the meaning of behaviour. Reframing can determine if I focus on what I’ve lost or what I can do with what remains.

How I frame something can greatly limit my options moving forward, or it can open a multitude of unimagined possibilities.

Through stories, our neighbour ladies took our family out of the pigeon-hole category of “enemy”, and deftly launched us into a whole new area of humanity in the neural pathways of the would-be killers.

Stories have often been used to reframe situations for a healthier and more peaceful conclusion.

For those who’ve survived great tragedy, reframing is where they find the life-giving breath that restores the heart, restores the intellect.

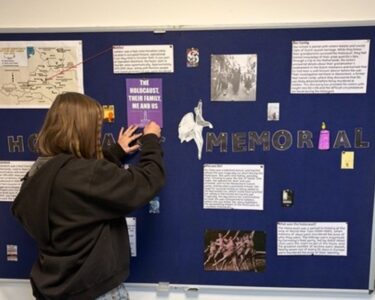

Finally let me end this story with the turbo-fuel that powers the strategy of reframing for me. It’s called “finding the good”. In the worst of situations there is always someone doing something good, something kind, something selfless. Every day I go looking for that, both at home and globally. When I find it, I then find a way to be part of it and in turn we shift our thinking – away from MY world, to OUR world and through it realise and live out a new global and civic vision ‘OUR world would be better WITH “you” in it’. We can all make a difference and contribute, but it is to our teachers and schools that I look to, supported by organisations like the UCL Centre for Holocaust Education to equip and empower young people to safeguard the future by learning about the past. It is my profound belief and hope that together, with such a personal and communal shift, this Genocide Prevention/Awareness Day, we can indeed make genocide ‘history’.’

Carl Wilkens – Co-founder/Director, ‘World Outside My Shoes’

Find out more via: http://www.worldoutsidemyshoes.org/ or follow @CarlWilkens #ImNotLeaving