Francis McMahon, Director of Progress and Beacon School Lead Teacher, Woodhey High School

This year, Woodhey’s history team has been working to embed narrative more deliberately into our schemes of learning. Whether through survivor testimony, class readings or carefully reconstructed historical voices, we have found that story-based teaching not only clarifies complex history but also creates the emotional and moral engagement essential for genuine understanding. We have been making the macro micro.

History teachers face a familiar dilemma. Time is limited, content is expansive and there is always pressure to cover large amounts of material at speed. Nowhere is this felt more acutely than in Holocaust education. The Holocaust is the most heavily researched historical event in the world. As a result, teaching can easily become overloaded with abstract facts and depersonalised statistics. For students, this can feel overwhelming and distant.

Narrative helps to counter this. Stories slow the pace. They introduce students to individual lives. They allow learners to step into lived experiences rather than hover above them. Testimony provides a direct human connection: it brings history to life, evokes empathy, challenges assumptions and serves as a moral witness to events that must never be forgotten.

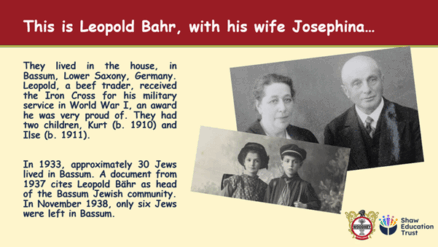

We are proud of how narrative has become central to our Holocaust curriculum. Our expansive case study on Rumkowski in RE, our exploration of spaces of memory, and our use of the stories of Leon and Else have all helped students understand key moments such as the November Pogrom, ghettoisation, the actions of the Einsatzgruppen, Riga, Babi Yar, Belsen, extermination and remembrance. One of my favourite lessons explores the November Pogrom through the story of Josephina and Leopold Barr. Through the life of this one family, students grasp the wider significance of the event with far greater clarity. The story of Trochenbrod, inspired by UCL’s own lesson on the topic, is another powerful example. Through the daily life of a thriving and joyful Jewish town, students confront the reality of the Holocaust by bullets in a way that raw statistics alone could never achieve. A forest clearing, a paved street, a postmistress and a schoolyard allow students to imagine life before its destruction. The loss then becomes not only understandable but deeply felt. We felt this was something worth sharing not only across faculties in our school, but also across our trust.

CPD and Whole School Impact

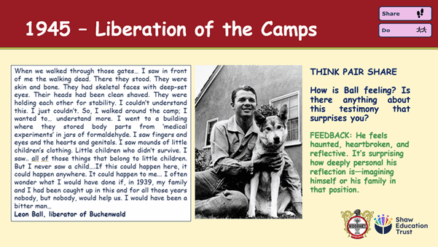

To strengthen this approach, we have delivered a sequence of CPD sessions to staff across the school and our wider trust. These included an hour-long session on narratives within Beacon School practice delivered to subject leaders across the trust, faculty-based CPD on narrative construction and a whole-school session focused on the use of testimony. In all three, our message was clear: teach the Holocaust one story at a time. Staff explored a model lesson sequence beginning with individual voices. Frank Cohn describing political street violence in 1933. A young girl suddenly frightened of the language she once spoke. Flora Singer recalling the final family photograph taken before the Shoah. Leon Ball, recounting horrific images of liberation. Each narrative acted as a doorway into the political, social and cultural forces shaping the 1930s. It’s heartening that staff have shown such enthusiasm in engaging with this topic, and we’re loving continuing to embed our good practice school-wide and trust-wide, as well as within our subject. This is all underpinned by a strong culture of student voice.

Transferable Skills and Literacy

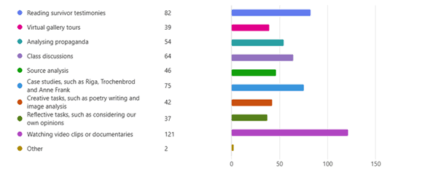

When conducting student voice on our Holocaust curriculum, we asked students what supported their learning most strongly. Reading survivor testimony, watching short documentary clips and engaging with case studies were chosen overwhelmingly. This confirmed what we suspected, but it also revealed something broader. Narrative-based learning was not only improving historical understanding but also fostering engagement.

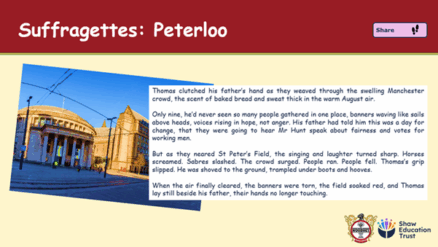

Narrative and testimony are essential pedagogical strategies that build the disciplinary literacy required for success in history. They raise reading ages. They strengthen inference and critical thought. They provide models for effective historical writing and foster empathy without losing academic rigour. At Woodhey, our History Team’s primary aim this year is to share this approach with every subject because if every teacher spent just three minutes per lesson reading with students, the cumulative total would be fifteen minutes of extra reading each day, seventy-five minutes per week and almost fifty hours per academic year. This has the potential to improve reading ages significantly and to close gaps for our most vulnerable learners. Indeed, we are already seeing this translate into stronger outcomes, particularly for disadvantaged students, and because of this success we have begun to apply these strategies across the entire history curriculum. In our First World War unit, students encounter a new poem every lesson. In the Suffragettes scheme of learning, they follow fictionalised figures who observe events from the shadows. In the Industrial Revolution, they read short narratives about Manchester workers as the city changes around them. In all topics, Narrative helps students connect, understand and remember.

Conclusions

When students analyse testimony and follow narrative threads across time and place, they practise the kind of deep reading that improves comprehension, vocabulary and inference. These are the precise skills needed across the curriculum and in their GCSEs. At a time when reading ages nationally lag chronological age, narrative provides a powerful tool for closing the gap. Testimonies and historical narratives expose students to complex, authentic language that goes far beyond transactional writing. Students who struggle with abstraction can access the bigger picture more confidently when anchored in the life of an individual or community. Their empathetic understanding becomes historical understanding, and their reading becomes analytical thinking. At least, that’s the aim!