‘I’ve said in ‘The Missing’ that writing poems is like going into another room, where you can think in ways that are different from when you write history or documentary.

Poetry gives you the permission to ask questions but you don’t have to answer them. You can leave gaps for ideas or feelings that you don’t fully understand yourself. You can try to go into other people’s minds and imagine what they think.

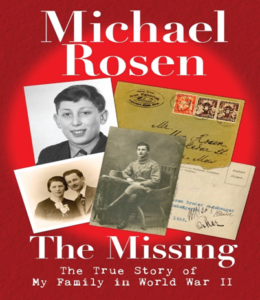

‘The Missing’ is about me trying to find out what happened to my father’s uncles. Bit by bit, with some luck, some coincidences and secrets kept in the family which only came into the open when old people died, I pieced together a horrific story of these two men (one of whom was married) fleeing across France, escaping a kind of net, being arrested and deported to the killing camp of Auschwitz. As I discovered things, I found I could write about them as facts, as events. But I also found that this didn’t explore or imagine how people might have felt. And I also found that it didn’t explore the ironies of the situation.

For anyone finding out about their relatives, you will find poetry gives you permission to ‘talk’ to these missing relatives. You can even pretend to be one or more of them! In one of my poems I start by saying ‘Dear Oscar…’ as if it’s a letter to my father’s uncle. And then I ask him questions. You may find that if you ask several or many questions, it starts to become a kind of story. There is a sequence, perhaps in order of who things happened that you can tell with questions.

Something else you may find out is that there might come a moment when you realise that history, and poetry are just words. So, if people are absent, one way we can bring them back, is by talking about them or talking to them. I believe that this is a good and comforting thing to do and it can sort out in our minds how we feel about past events.

How can it do that? Our minds seem to be a complex place where thoughts and feelings rush about but when we write, there seems to be a way in which it helps us to put those thoughts and feelings into an order. And this order, for the time being, helps us with things that hurt or disturb us. It may only be in the moment of writing the poem, or it may come when we read it back to ourselves, or when we share it with others. I think it’s a bit like putting your thoughts and feelings on a mirror. You can see yourself. And it doesn’t have to be the be all and end all. You can write something from a different point of view tomorrow.

Writing poems about my father’s uncles, above all, helped me see and feel the awful way in which the Holocaust hunted down innocent people, how chains of command went from on high all the way down to a man being arrested in a tiny French village where he was staying. How this totally ‘extraordinary’ act of brutality was at the very moment that it happened, ‘ordinary’. That’s what’s called a ‘paradox’ and poetry is often good at showing paradox.’

Among the poems that feature in ‘The Missing’ is this, originally written by Michael to mark Holocaust Memorial Day in 2018 – it’s called:

‘The Absentees’

There are gaps,

there are blanks,

in the house

of my life;

there’s a face,

nothing more,

something gone

from my life.

She was here,

he was there,

in the rooms of my life;

there’s a place

for them both

in the words of my life.

(c) Michael Rosen, taken with permission from The Missing, Walker Books 2019