Lesson 13 enabled me to explore with students the historical significance and contemporary relevance of the Holocaust today. I asked students, ‘How should the Holocaust be remembered?’ Students would be given the opportunity to analyse a memorial to ascertain an opinion, engage in a matching group activity and independently construct a balanced argument about memorialisation and commemoration in writing. This approach supported students developing historical skills in source analysis and refined their understanding of interpretation and representation.

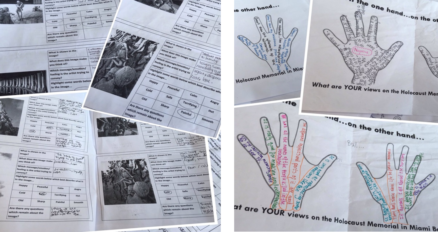

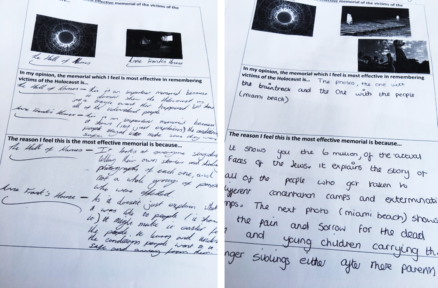

Students responded well to this task, although I wonder if it could be done a little differently. They needed more ‘run up’ to analysing the sculpture as art work – perhaps I could have used the Frame of Questions from the Pre-War Jewish Life lesson and used the Miami Beach Memorial images as a starter to remind them of aesthetic analysis, then moved straight on to the Around the World activity lesson? Students responded really well to the ‘on the one hand’ (GCSE style) question and were mostly able to complete it, using information about the memorial. There were some interesting discussions about why some students didn’t find the memorial effective and why some did. Some that didn’t find it effective were able to select information from previous lessons about aspects of the Holocaust that the memorial didn’t show but were respectful of what it did.

Students responded well to this task, although I wonder if it could be done a little differently. They needed more ‘run up’ to analysing the sculpture as art work – perhaps I could have used the Frame of Questions from the Pre-War Jewish Life lesson and used the Miami Beach Memorial images as a starter to remind them of aesthetic analysis, then moved straight on to the Around the World activity lesson? Students responded really well to the ‘on the one hand’ (GCSE style) question and were mostly able to complete it, using information about the memorial. There were some interesting discussions about why some students didn’t find the memorial effective and why some did. Some that didn’t find it effective were able to select information from previous lessons about aspects of the Holocaust that the memorial didn’t show but were respectful of what it did.

Building on the previous lesson, I designed lesson fourteen, to address the question of ‘How has the Holocaust been remembered around the world?’ This lesson enabled students to analyse more memorials to enrich their opinions, develop their own Holocaust definitions and write a justified/supported historically informed opinion about memorials. This involved significance, source analysis and understanding interpretation and representation.

Students seemed to enjoy the nature of this more creative, historically informed, task – there was a matching activity which got students curious about the places featured, and also a cut/stick activity, which meant they could show their opinion in an individual way. Everyone was being extremely respectful of each other’s opinion. There haven’t been any cases of students mocking each other and where students wanted to challenge each other’s thinking inappropriately, it has instead been done in a calm, measured, respectful and mature way.

Next, I wanted to challenge my students think about memorials, commemoration further. Using their historical knowledge and understanding, I wanted students in lesson fifteen to apply that to the questions of ‘How should we remember minority groups’ and the Holocaust. This would refer back to our Timeline lesson, our definition of the Holocaust and draw upon findings of the Centres’ 2016 student research regards Jews and other victim groups the Nazis persecuted and murdered (You can find out more here: https://holocausteducation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/1.-Non-JewishVictimsOfNaziPersecutionMurder-download.pdf)

Next, I wanted to challenge my students think about memorials, commemoration further. Using their historical knowledge and understanding, I wanted students in lesson fifteen to apply that to the questions of ‘How should we remember minority groups’ and the Holocaust. This would refer back to our Timeline lesson, our definition of the Holocaust and draw upon findings of the Centres’ 2016 student research regards Jews and other victim groups the Nazis persecuted and murdered (You can find out more here: https://holocausteducation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/1.-Non-JewishVictimsOfNaziPersecutionMurder-download.pdf)

Throughout the lesson students contributed actively to whole class analysis of memorials, they engaged in a Blackout activity and produced an individual creative response combining themes/words which best described persecution of homosexuals. This lesson sought to develop source analysis, interpretation, representation and significance,

Again, I am not sure about this task being ordered in the way that I taught it. Perhaps I can hand out the memorials and do a ‘marketplace’ analysis? Students enjoyed the ‘Art with Words’/typographic art aspect of the lesson and commented on the Blackout activity, which was something they enjoyed doing, as it was ‘different’ to just highlighting text. I magpie’d this from one of the Teaching feeds on Twitter a few weeks ago, and thought it was a great way to sift through text (students must actually read everything to work out what they don’t need). This method could be used in future, when there are long pieces of contextual information to get through.

Ideally, I need to look at how the ‘minority groups’ identified all the way back in the timeline lesson could be recapped and looked at in the same way. What I did worked well, but I would have liked to look at more than just persecution of homosexuals in depth. Could I look at one memorial per victim group? I am not currently not sure how this would work, but it is something I can keen to keep and develop.

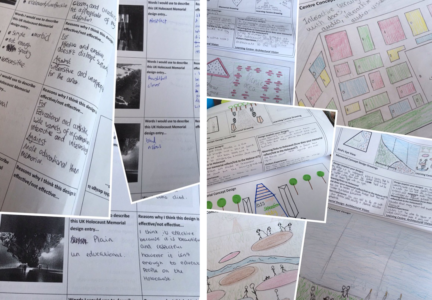

Lesson sixteen was created due to national circumstance – at a time when the UK Holocaust Memorial Foundation were shortlisting their memorial competition designs. So, combining historical knowledge, their understanding of memorials and importance of commemoration, I would ask students ‘How has the UK committed to remembering the Holocaust? – and indeed, why? This would build on source analysis, significance, interpretation and representation.

Lesson sixteen was created due to national circumstance – at a time when the UK Holocaust Memorial Foundation were shortlisting their memorial competition designs. So, combining historical knowledge, their understanding of memorials and importance of commemoration, I would ask students ‘How has the UK committed to remembering the Holocaust? – and indeed, why? This would build on source analysis, significance, interpretation and representation.

Students were attentive and threw themselves into this task – they seemed genuinely interested in each of the shortlisted designs and actively listened to the short descriptions of each. I’m pleased I spent the time putting the resources together for this, as students responded carefully and well to the scaffolded approach of responding to the memorial designs and the depth of their analysis revealed the depth of the knowledge and their growing confidence and ability to apply their understanding. I found students were now a lot more comfortable in giving their opinion, as an individual, and saying ‘why’. They’re also hugely respectful of each other. This task however, only took half a lesson, so I had to move straight on to the design task. It worked well, as students could refer to the design’s they found effective and thought about why. I could flick through the shortlisted designs with them and have conversations with them, making sure they could articulate why they found elements of the designs successful.

So, the planned lesson seventeen – which was entitled ‘How can we design a UK Holocaust memorial’? – was embarked upon earlier than expected. Students undertook this task well and were enthusiastic about the concept of designing their own memorial and an accompanying learning centre. The portfolio needs a tiny bit of work/I need to explain the different ideas with more clarity, as a lot of time was spent going around explaining the mechanics of the design portfolio to different tables. This could be easily adjusted though, and my explanations didn’t affect the design concepts. Students are really clear that they want the design to incorporate elements of education and contemplation – what they all think is important is that the Memorial/Learning Centre needs to leave visitors with historical information about the Holocaust, the people/communities (both pre- and post-war) and testimonies/sources. Students are really thinking about the contemplation element – they like the idea of something interactive and something that ‘grows’ over time. This seems like a great lead-in to the creative task, although could equally be a task which shows their understanding of the Holocaust. I need to think about how I could factor this in for next year, if we were to shorten the amount of time for the scheme of work/learning, due to teaching/timetable constraints, but it certainly supported and fostered their interpretation, representation and understanding of significance.

So, the planned lesson seventeen – which was entitled ‘How can we design a UK Holocaust memorial’? – was embarked upon earlier than expected. Students undertook this task well and were enthusiastic about the concept of designing their own memorial and an accompanying learning centre. The portfolio needs a tiny bit of work/I need to explain the different ideas with more clarity, as a lot of time was spent going around explaining the mechanics of the design portfolio to different tables. This could be easily adjusted though, and my explanations didn’t affect the design concepts. Students are really clear that they want the design to incorporate elements of education and contemplation – what they all think is important is that the Memorial/Learning Centre needs to leave visitors with historical information about the Holocaust, the people/communities (both pre- and post-war) and testimonies/sources. Students are really thinking about the contemplation element – they like the idea of something interactive and something that ‘grows’ over time. This seems like a great lead-in to the creative task, although could equally be a task which shows their understanding of the Holocaust. I need to think about how I could factor this in for next year, if we were to shorten the amount of time for the scheme of work/learning, due to teaching/timetable constraints, but it certainly supported and fostered their interpretation, representation and understanding of significance.

By lesson eighteen I wanted to explore with students how we can use art and design to creatively respond to our historical learning about the Holocaust. For me, these ‘creative’ lessons are not unusual. However, some careful meetings have had to take place with the rest of my department team about giving students the opportunity to be ‘creative’ within our history classrooms – and the scope for students to develop and develop key history skills in a non-traditional way. Having the freedom to express oneself in an environment most used for history lessons will be unusual for both staff and students and I was very mindful of this for my History team.

I needed to make sure that a) staff felt comfortable with the logistics of creative making b) staff had access to required resources c) if applicable, an alternative space in which to work and d) the opportunity for preparatory work with students, introducing them to the concept of creative making in a different environment (again, if applicable).

I needed to make sure that a) staff felt comfortable with the logistics of creative making b) staff had access to required resources c) if applicable, an alternative space in which to work and d) the opportunity for preparatory work with students, introducing them to the concept of creative making in a different environment (again, if applicable).

I was also mindful of the integrity of subject discipline – students needed sound and secure historical knowledge of the Holocaust and that skills demonstrated throughout the creative process were historically sound and rigorous as ultimately it’s about their becoming better historians. I was also mindful of the ‘creative making’, but also equally conscious of the need to provide students with the opportunity to respond in a truly creative way to the task.

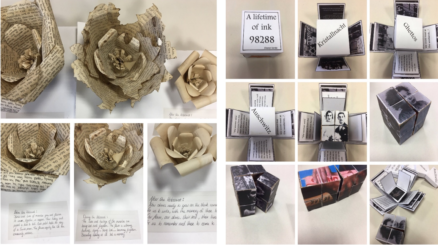

There are elements of learning about the Holocaust which are inexplicable, dimensions of the Holocaust that are indescribable, ineffable, and I wanted to provide students with an opportunity to express their learning about the Holocaust in a way other than words. I was also mindful of the fact that there are many ways in which students can be assessed and that should include not just the ‘knowledge’ but crucially the way in which the knowledge has been applied to the outcome. It would be an understatement to say that I was not to be disappointed.

This type of expression of knowledge is transformative. I have always strived for a creative History classroom, but I have never really stretched the creative boundaries this far. This creative response will become fundamental to how I move forwards and how I can use this in many more opportunities for learning. The enthusiasm of the students and staff was something that had not been experienced before and there was an ever-present desire to ‘do the knowledge justice’.

This type of expression of knowledge is transformative. I have always strived for a creative History classroom, but I have never really stretched the creative boundaries this far. This creative response will become fundamental to how I move forwards and how I can use this in many more opportunities for learning. The enthusiasm of the students and staff was something that had not been experienced before and there was an ever-present desire to ‘do the knowledge justice’.

I found myself equally inspired, humbled and motivated when looking at the phenomenal standard of work provided by my students and shall strive to continue this at every opportunity.

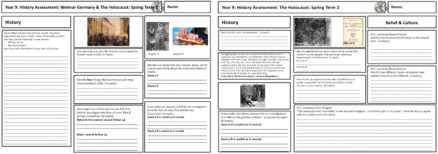

So how will I move forward following my first cycle of the scheme of work/learning? Beyond the tweaks of my reflections, assessment is a key area for development.

Is it possible to assess what students know and understand about the Holocaust? In short, yes of course, but the assessment model finds itself needing to ‘fit’ alongside our college assessment requirements. At the end of each half term, the requirement is that students undertake a formal assessment which gives them a percentage score (knowledge) and an indication of progress in terms of application of knowledge. This will remain I think, a fluid document, as I need to prepare students for the language of the GCSE. This will in turn, influence the language of the scheme of work/learning; the knowledge needs to be retrieved regularly and the knowledge needs to be applied cumulatively, in order to best prepare our learners for GCSE study. This does not mean for one minute that the creative element of the scheme of work/learning should be taken out, as I think it is fundamental for student expression and provides an important opportunity for them to express themselves in ways other than words.

This year will be the ‘pilot’ year for the new assessments, and we are reviewing them each half term, to ascertain whether they are a) rigorous enough and b) an accurate reflection of student knowledge and application of knowledge and c) allowing our students to progress over time.

By Charlotte Lane