Sunday, 9 December 2018, marked the 70th anniversary of the adoption by the United Nations General Assembly of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

As we formally recognise this important milestone, the Centre believes it provides an appropriate moment to consider the legacy of the Convention and its forefather, Raphael Lemkin, as well as the challenges and opportunities it presents us with in the present day. Professor Stuart Foster, our Executive Director commented thus:

“Genocides occur because perpetrators place no value on the rights and humanity of ‘others’. So, it is imperative that we educate for a world in which understanding overcomes ignorance and empathy prevails over brutality.”

We are delighted therefore, as a Centre, to be able to recognise this anniversary by sharing the reflections of Lord Bourne, Parliamentary Under-Secretary and Minister for Faith, and of The Rt. Hon Lord Pickles, Special Envoy for Post-Holocaust Issues and co-chair of the United Kingdom Holocaust Memorial Foundation.

The phrase ‘genocide’ was first coined by Lemkin in 1943. By this time, many of those who lost their lives in the events we now call “the Holocaust” had already died – with most shot into mass pits in Eastern Europe, gassed in specially constructed fixed-installation facilities in the Operation Reinhard death camps, or succumbed to disease or starvation in overpopulated, impoverished ghettos. Among these victims were members of Lemkin’s family, whom had remained in Poland after he had fled to Sweden in 1939. For Lemkin, then, the destruction of European Jewry was a very personal matter, and it was one he sought to classify and understand through his magnum opus, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe(1944). Yet in formulating the term genocide, Lemkin was not just concerned with the tragic fate of Europe’s Jews; rather, he was seeking to construct a conceptual framework for understanding the experience of other groups targeted by the Nazi regime (in particular, the Poles). Moreover, as his thinking developed, Lemkin also sought to position the policies of Nazism into a longer-term context that took due cognisance of mass atrocity throughout human history.

The passage of the Genocide Convention was an enormously significant moment in the history of international relations. As much as obliging those who ratified or acceded to the treaty to prevent and punish genocide, the Convention provided a normative framework which has shaped our post-war world. Yet, for all its positives, upholding the Genocide Convention and enforcing its obligations has been challenging. In crude terms, the Convention has not stopped genocide from occurring, nor has it spurred countries into action when the first signs of genocidal activity have appeared. In fact, if anything, the reverse has often occurred. Faced with genocide, or with evidence that genocide is looming, the international community has often become pre-occupied with differing interpretations of the Convention, or found ways of ignoring it altogether.

For young people who know and understand what genocide is and what it entails, this is peculiar, confusing, and nonsensical in equal measure. Yet our student research of 2016 also indicates that the majority of young people do not actually know what the word ‘genocide’ means. When asked to select the correct definition for the word, only 45.8% of all respondents did so correctly, and it was only among older students (16-18 year olds) that this climbed above 60%. Given the Holocaust has been a permanent fixture in the National Curriculum since 1991, and there is a long-standing tendency for the Holocaust to be presented as the exemplar or paradigmatic genocide, this raises pressing questions. Some of these relate to whether the extermination of Europe’s Jews is being accurately positioned with mankind’s long, dark history of violence and brutality. Others concern the conceptual frames erected around “the Holocaust” in classrooms and wider culture, and the extent to which these may actually detach the Holocaust from its root phenomenon: genocide. And others still touch on the reasons why we are choosing to teach, learn and remember certain historic instances of genocide but not others.

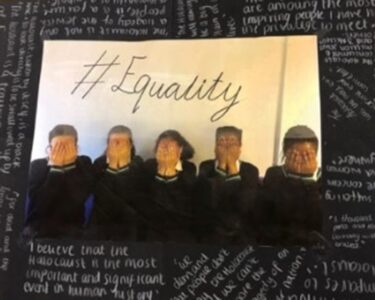

Teaching and learning about genocide – be it the Holocaust, or those that came before or after it – is not an easy endeavour. Here at the Centre we work on daily basis helping to support those who wish to develop their practice and make their students’ encounters with this phenomena as meaningful and productive and possible. And, during the course of our work over the last decade, we have seen evidence of truly inspirational teaching and learning. Some of these examples are the product of imaginative and innovative teaching; others have been driven by young people themselves; all are testament to what can be achieved when there is both the will to explore these complex and complicated issues, and the means to do so. On this seventieth anniversary, we are very pleased to share some of these examples with you here: