Dr Andy Pearce’s Op-Ed was recently published on School Management Plus

The Curriculum and Assessment Review asks a simple question: what do we owe every young person? In answering that question, it was encouraging that Professor Becky Francis’ review acknowledged the enduring importance of Holocaust education.

The Review is unequivocal that we should teach and learn about the Holocaust. But two critical questions remain: why and how. These may appear to be simple and straightforward to answer. In reality they are not.

In September 1991, England’s first national curriculum came into force. With it, teaching about the Holocaust became compulsory in state-maintained schools. This decision signalled learning about this event is not optional. But why this should be the case was not made clear at the time. Nor was it made in revisions to the curriculum since.

Within this vacuum, one argument became popular. That simply by teaching about the Holocaust, young people would inevitably learn its lessons. It was, and it remains, an alluring idea. But there is no agreement about what the lessons of the Holocaust are. Even if there was, education is more complicated than this idea presumes.

The answer to why teach the Holocaust is not because it teaches us lessons. We should teach and learn about the Holocaust because by doing so we acquire fundamental insights into who we are as human beings. We learn more about the human condition. We confront dark, but unavoidable, truths of what we are capable of.

These are compelling and immutable reasons why the Holocaust should be taught. They are reasons that have but a deeper resonance as the last survivors become fewer in number each year. And they are reasons that have added salience in our contemporary world.

Because this is not simply about history. With growing levels of online conspiracy belief, misinformation and disinformation shaping how young people encounter the world, the Holocaust’s insights and perspectives into what it means to be human have added weight. Holocaust education cannot solve all of our ills. But it can make a vital contribution to crucial endeavours such as building media literacy and developing critical thinking.

What, then, of the how?

We know from research that the belief the Holocaust can be used to teach us lessons has long shaped how it is taught in schools. And yet research also shows this approach has played a part in many young people having significant gaps in their knowledge of the Holocaust and harbouring problematic misconceptions.

Evidence suggests then, that it is high-time that we rethink how we teach and how students learn about this subject. Having expertly trained teachers, who are research-informed and armed with intelligently devised resources, is an important first step. It helps create opportunities for students to engage deeply and empathically with this history.

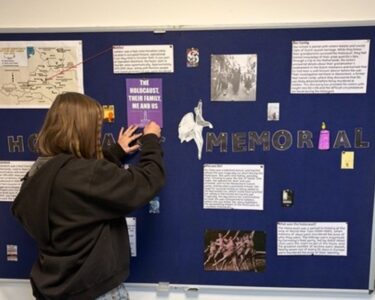

At the UCL Centre for Holocaust Education, we support the development of such teachers. Funded by a unique partnership between the Department for Education and Pears Foundation, we provide a national programme of training that helps teachers at all stages of their career to develop confidence, subject knowledge, and expertise in how to teach this challenging past. To date, over 34,000 teachers and 267 Beacon Schools have benefited from our training and transformed their approach to Holocaust education.

And we have robust evidence to show that it works. Students who are taught Holocaust history through research-informed approaches are better equipped to interrogate sources, recognise falsehoods and understand how problematic narratives are constructed.

Such outcomes have never been more important. Students increasingly arrive in the classroom with preconceived ideas about the Holocaust, often shaped by what they have encountered on social media. Teachers are consistently telling us they are meeting denial, distortion and simplified narratives that strip away complexity.

The task for teachers is therefore twofold: to help students develop the knowledge and skills required to understand the Holocaust, and to enhance their media literacy and critical thinking so they recognise misinformation, can test claims against evidence, and confront the continued threats posed by extremism and prejudice. For that, teachers need expert support – from their schools, from the system, and from training providers committed to evidence-based approaches.

Professor Becky Francis was right. A national curriculum is a statement of what we owe every child. And as we near the 35-year milestone of the Holocaust in the national curriculum, her recommendations are welcome.

But reinforcing the importance of Holocaust education in school curricula is not enough. We have to be clear why students should learn about it in 2025. We need to explain how it can be taught effectively in our current age. And we must sustain investment in teacher development and the research infrastructure that ensures teaching this subject remains evidence-led.

As survivor voices fall silent and misinformation grows louder, it is only by taking these actions that we will help pupils think critically in an increasingly noisy world.

Dr Andy Pearce is Director of the UCL Centre for Holocaust Education