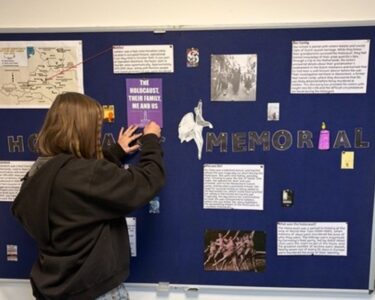

On 22 September, we launched the first Alumni Beacon Community (ABC) session of 2025–26 — a space for alumni teachers to reflect honestly, share priorities, and connect within a supportive community of practice. Colleagues brought pride, frustration, and curiosity to the table, each naming one focus for developing their Holocaust teaching and learning this year. It wasn’t about polished answers, but professional generosity — the kind that invites growth, not perfection.

Here, we hear from two of those alumni: Katy Fenwick, tackling a persistent misconception in mainstream provision, and Gary Barker, exploring assessment and accessibility in a specialist setting. Though their contexts differ, both share a commitment to reflective practice and improving student experience. Their insights offer not a blueprint, but a window into the real work of refining Holocaust education.

Challenging the ‘Hitler-centric’ narrative of the Holocaust in Year 9

As a UCL Beacon School for Holocaust Education, we consider ourselves to be in a strong position to teach this subject. Croydon High School for Girls Scheme of Work is launched after Holocaust Memorial Day, when pupils participate in workshops following the story of Leon Greenman, set against the backdrop of the Holocaust timeline.

The following Scheme of Work includes seven one-hour lessons on the Holocaust, covering the long history of antisemitism, the actions of others, the role of bystanders, and the lack of intervention from other countries.

It is, therefore, somewhat disheartening that research conducted by UCL, based on our students’ survey responses, still shows that some persist in believing Hitler alone was responsible for the Holocaust, and that Britain was largely unaware of these events until after the war. This is not simply a matter of pupils choosing not to believe me, their lessons are evidence-based, allowing them to examine the facts for themselves. More significantly, their end-of-unit essay assessments, titled “To what extent is Hitler solely responsible for the murder of six million Jews during the Holocaust?”, show that they are capable of identifying the role played by the long history of antisemitism and the failure of others to act, whether that be a country like Britain or an individual bystander.

However, a year later, when completing the UCL survey, this understanding appears to have faded, with students reverting to a ‘Hitler-centric’ narrative and seeming unaware of the gaps in their knowledge. I know we are not alone in facing this problem, which is also disheartening. The Centre’s research has shown that pupil misconceptions are especially resistant to change.

So, what – if anything – can we do about this?

Firstly, we can reconsider the assessment. Perhaps the title of the essay encourages the ‘Hitler-centric’ view by placing him at the forefront of the question. Maybe shifting the focus towards the inaction of others, to emphasise that this was a societal crime, would help. However, I suspect that once in Year 10, the assessment is largely forgotten, and the prevailing societal view – that this was solely a Nazi crime – becomes ingrained. The plethora of books, films, and documentaries about Hitler, the Nazis, and the Holocaust tends to reinforce this message, and their History lessons alone cannot counter it.

Secondly, perhaps writing an essay is not the most memorable way for pupils to retain their learning. (For context, they do complete other smaller assessments throughout the Scheme of Work, but this is their end-of-year examination.) Our Year 10s and 11s participate in a debating competition, and a question such as “To what extent was the Holocaust a societal crime?” would be both valid and engaging. This could help reinforce prior learning and challenge the ‘Hitler-centric’ narrative.

I am not sure that these small measures will result in a seismic shift in pupil understanding, it sometimes feels like an uphill battle, but it is a starting point, and we will continue to reflect and refine. We look forward to sharing and updating at a future ABC”

Katy Fenwick, Head of History, Head of Year 12

Curriculum and Assessment at Hestia School

At Hestia School, each academic year brings new challenges due to the diverse needs and abilities of our pupils. While smaller class sizes might appear easier to manage, the complexity of teaching a group with reading ages ranging from 6 to 16 requires significant differentiation and flexibility.

Each year, we invest time in understanding our pupils to adapt lesson content and delivery. Based on pupil profiles, we decide whether to implement a six-lesson or full fourteen-lesson programme of study. In recent years, our curriculum has shifted towards vocational learning, moving away from traditional academic models. This change has prompted a review of how we assess pupil progress.

We have transitioned from assessments focused on knowledge recall and written output to a more inclusive, skills-based approach. Our new model uses “I can” statements as Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), allowing pupils to demonstrate understanding in varied ways. For example, in our Holocaust unit, pupils might be assessed on their ability to describe events, use specific facts, paraphrase sources, or quote directly from materials.

Progress is measured using four descriptors:

- Emerging

- Developing / Supported

- Expected

- Mastered

This approach ensures that all pupils, regardless of starting point, can have their progress recognised and celebrated. It supports a more personalised and meaningful learning experience, particularly for those with SEND.

As this is the first year of implementation, the model will be reviewed as part of our subject evaluation and development planning. We aim to refine the approach based on pupil outcomes, staff feedback, and its impact on engagement and accessibility.”

Gary Barker, Assistant Headteacher, Head of Post 16

We’re grateful to Katy and Gary for their thoughtful, honest contributions. Their reflections speak to the real work of refining Holocaust education — shaped by context, cohort, and professional judgement. These aren’t definitive answers or endorsed models, but timely responses to the challenges they face in their settings. Their willingness to trial, adapt, and move practice forward is what matters most. These concerns aren’t unique, but every school and classroom is different — and it’s heartening to see colleagues seeking progress. The ABC session was rich, insightful, and energising, the professional sharing and support was incredible to be part of, and many ideas were exchanged.

We’d love more Beacon alumni to join us next time: Wednesday 19 November, 4pm. Whether you’re ready to contribute, curious to listen in, or simply keen to reconnect with your community, you’re warmly invited.