As many of us appreciate, the provision of Holocaust education is not an area of work designated only to History departments and colleagues. In this vein, we are delighted to showcase two examples of work, very different in their approach, carried out within alumni RE/RS Departments.

Building an RE Holocaust Scheme of Learning at Woodhey High School – Francis McMahon, Beacon School Lead Teacher

“Building a curriculum:

As any Beacon School Lead Teacher knows, designing an effective scheme of learning for Holocaust education is an immense task. The scholarship is vast, the subtopics are seemingly endless and there are hundreds of thousands of images, testimonies and archives to trawl through; and when all that is done, it must be condensed down into a dozen or so lessons and delivered to Year 9 in a way that teaches them something about something. Early on in our Beacon School journey, we came to conclusion that while we felt we had mapped out a strong scheme of learning for History, there were threads of philosophy we wanted to unpick further – threads of forgiveness, morality, righteousness, godliness and religiosity. Things that, for all the best of intentions, are not always given priority in a history classroom. Resultantly, we took the decision to expand Holocaust Education into the RE classroom, by building a parallel scheme of learning that would run alongside our History scheme.

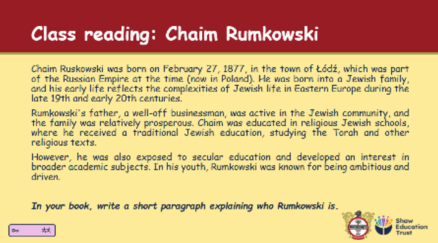

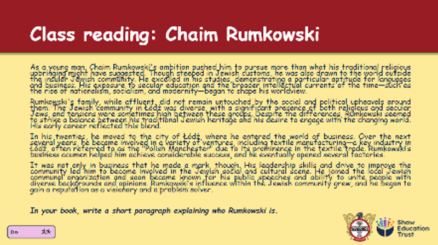

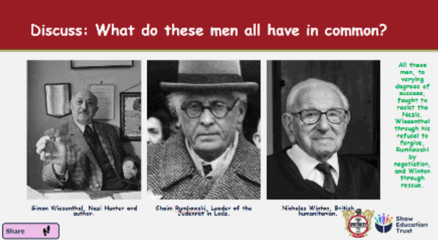

From the outset, we were clear that this couldn’t be a second History scheme in disguise. The RE curriculum needed to be different. We wanted students to wrestle with ideas of moral courage, divine absence, and religious identity in the face of systematic dehumanisation. To support this, we built the scheme around the stories of two individuals: Chaim Rumkowski (a morally complex, flawed, and deeply human figure whose leadership of the Łódź Ghetto is as controversial as it is confounding) and Simon Wiesenthal (a Holocaust survivor, Nazi hunter and author, who struggles with the concept of forgiveness while navigating guilt). We felt these narratives provide a lens through which students could encounter the Holocaust not as statistics, but as human experience.

Rumkowski’s story in particular runs like a thread through the first seven lessons of our scheme. It offers students a narrative anchor: a recognisable world with recurring characters, places, and moral dilemmas. We started small – we introduced students to life within the ghettos across six lessons, and within each of them we provided a tiny snippet of Rumkowksi’s narrative, allowing students to discover Rumkowski in real time, removing the sense of his inevitable demise from the narrative.

|

|

|

In Lesson 7, we reveal to students his role in the mass deportation of Jewish people from the Łódź Ghetto and ask students whether – given the impossible choices he faced – his decision was justifiable. No longer just a controversial figure, students now must wrestle with exploring the complexities of a horrific decision made by a man they have lived with for seven weeks. Teaching Rumkowski in this manner provides a vital context for discussing choiceless choices. This approach allows students to move beyond surface-level facts and engage meaningfully with the Holocaust’s theological and moral implications, which then serves as a springboard for exploring the concept of forgiveness through Wiesenthal’s ‘The Sunflower’ – history’s forgiveness of Rumkowski, Wiesenthal’s forgiveness (or lack thereof) of the Nazi, and ultimately – in the third act of our scheme of learning – our own forgiveness of Britain for their role in the Holocaust.

|

|

|

We are delighted to be able to share our RE scheme of learning via our school sharepoint, or you can email Francis to discuss this scheme of learning further.

Supporting non-specialists:

Delivering such complex content in RE – a subject where Holocaust education has traditionally been less prominent – was not just about building a scheme of learning. It also meant we had to think carefully about how to support our teachers. Through a combination of UCL-led CPD, detailed lesson guides (each of our lessons have two versions, a version for students to access and a staff version in which every question is pre-green-penned), and collaborative planning sessions, we’ve built staff confidence in handling sensitive material and navigating difficult conversations. Having a supportive Director of Faculty was key, too. Collaborating with our DOF on our UCL mid-point self-assessment process highlighted the importance of consistent opportunities for staff reflection. From this, we put into place weekly non-specialist drop-ins, provided all non-specialists with UCL textbooks, and began to undertake learning walks designed to spot good practice and share it amongst the wider teaching team. I am proud to say that our students who are taught by non-specialists within our faculty receive the same opportunities and education as those who are taught by specialist teachers. This is no easy feat, but we feel we have succeeded in pulling this off.

Our takeaway:

Opting to build two new schemes of learning has been an immense task, but it has shown us the value of teaching the Holocaust in different subject disciplines. While History continues to offer vital chronological and contextual knowledge by exploring testimony and interpretations, our RE scheme gives students the space to confront the enduring, unanswerable questions of belief, morality, and human nature. It allows them to ask, not only what happened to the Jewish people, but what happens to faith under persecution – and what responsibility we all carry in shaping a more just world. By the end of Year 9, our students have spent 40 lessons exploring the Holocaust. We are confident that this is time well spent.”

At All Saints, Mrs Kelly and colleagues’ scheme of learning includes opportunities for students to reflect on the impact of law changes upon the Jewish community in Germany and their sense of identity, belonging and as citizens.

“At the start of the lesson you explained what life was like for Jews in Germany before Hitler came to power. Now explain how and why Jewish life changed from 1933-38. Add examples of law changes and how Jews were identified and the impact that this had on them”.Here are example student responses to said task.1.Hi! My name is Aviva and I am a German Jew. Before 1933 and the Nazi Party my life in Germany was peaceful; I worked in a school as a teacher. My life was fun, ordinary and pleasant – I lived a harmonious life.I lived with my children and my husband who is also a German Jew and he had an office job.However after 1933, my life changed dramatically. Jewish people regardless of whether they religiously followed Judaism or not, were removed from work places. I was removed from my teaching job in 1936. In 1938:Jewish people were banned from becoming doctors.Jewish people had to carry identity cards which showed a ‘J’ stamp.Jewish children were denied education and banned from schools.In 1939 my family and I were forced into a ghetto that separated us from the rest of the German community.We were discriminated against and tortured and because of this as a German jew, I feel undervalued, as well as disappointed that the public have been easily influenced by the propaganda that continues to ruin the our world.

- Hi! My name is Sara and I am a German Jew.

Before 1933 and the Nazi Party, my life was great, I got to spend lots of time with my family and we were as free as other Germans that weren’t Jewish. I had a job teaching children to read and write. My life was interesting. I could have experiences like everyone else, it was truly amazing.After 1933 my life changed. Laws like the number of Jewish children being limited in school and later Jewish teachers getting banned from schools overall meant that I could no longer work in my job, or teach children like I always wanted to. I now feel as a German Jew that I am limited in the amount of freedom I really have, and my job being taken away did not help, leading for me to have to start borrowing money from other people just to try and survive.

- Hi. My name is Arie and I am a German Jew. Before 1933 and the nazi party my life was amazing we were all interconnected as a society. My life was filled with extravagant parties and lavish events. I never had any worries and spent most of my days surrounded by my family and friends. However, we didn’t know this was all about to change and leave a permanent loss on our lives. I had a job being a farmer. My life was very interesting. I lived in a house with my parents and my brother. I had many experiences and opportunities come my way. After 1933 our lives changed. Laws were changed many of us had our licenses taken off us, Jewish teachers were no longer allowed into schools, they are no longer counted as citizens this meant we had our rights stripped off us, we had no freedom and we were no longer in control of our own lives. i now feel as a German jew that I am invisible and not respected. As a citizen as a society we should respect each other and want the best for one other however this isn’t the case, I feel that I am an outsider and that I don’t belong In the community. A community is about being a collective we are not a collective.

- Hi my name is Helga and I am a German Jew. Before 1933 and the Nazi Party my life was normal. I had a job working in an office My life was interesting, I lived in a house. I had experiences such as making many memorise with my children going out with my friends and much more. After 1933 my life changed. Laws like not being allowed to have an education not being able to get married meant that I could no longer enjoy what I took for granted before. I now feel as a German Jew that I am underappreciate and no longer as important in society.

- Shalom, my name is Felix and I am a German Jew!

Before the Nazi Party came into power, my life was filled with extravagant parties and lavish events. My job was rather important and I was well valued in society. However one day everything began to change.Slowly, customers who had been loyal to my business for years slowly began to fade away, outstanding invites disappeared, and many lifelong friends and acquaintances all turned their back on me. In November of 1938 a law was commended that all Jews were no longer allowed to have their own businesses and sell their own goods. The new law meant that I was now unemployed, and I was slowly losing any money or goods I used to own, my house in the middle of my town was disregarded by

- Hi! My name is Perl and I am a German Jew.

Before 1933 and the Nazi party my life was amazing all of us (the German jews) were well integrated into the German society.I had a job as a seamstress and I was very happy and didn’t have any worries. My life was very interesting. I lived in a lovely two story house with my two beautiful children who I loved dearly. I experienced things like going on holiday abroad and make life changing memories that I will never forget. After 1933 life changed laws like the number of Jewish children allowed in schools is limited and jews have their drivers licences removed this made me and my children distant from the rest of the German society. Lots of my children’s relationships were being ripped from them just because of their religion. Building up this work, focusing on identity, community and belonging, and understanding the impact of Nazi legislation, students utilise their RE skills when looking at the idea of spiritual resistance in the Ghettos.