It was an honour and a pleasure to join Rob Rinder in celebrating his Honorary Degree on 20 May. To mark the occasion, Rob writes in Schools Week

Holocaust education is more vital than ever

Great educators know the best way to communicate the scale of the Holocaust is to ensure students connect with it on an individual level.

I’d always known, for as long as I can remember, that my grandfather was a Holocaust survivor.

But there was, within the unspoken rules of our family, an understanding that we didn’t ask directly for narrative history of his experiences. Bits of his story came out in fragments, but not the full story.

It wasn’t until Who Do You Think You Are? that I came to understand the enormity of his experience and that of his friends and family. Patterns began to emerge within the dark outline of the jigsaw of my understanding.

And through that I came to understand both the scale of the genocide itself but also the rich histories of the communities throughout much of Europe that were simply erased, including those which my grandfather had called home. The enormity of what had been lost became clear.

It was this experience that spurred me on to play a role, alongside an incredibly creative and committed team, in the making of My Family, the Holocaust and Me to explore it even more. The response to this documentary demonstrated the public appetite for a greater understanding of the Shoah as told through human stories and detail.

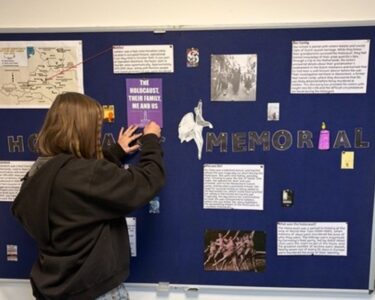

It is also why, in turn, I have become involved in an extraordinary educational project The Holocaust, Their Family, Me and Us which was developed by Royal Wootton Bassett Academy and expertly supported by the UCL Centre for Holocaust Education.

The project, which is organised by two incredible teachers Nicola Wetherall and Charlotte Lane, weaves human stories, including those of my family, into their work with thousands of students every year.

I am incredibly honoured to receive this week an honorary degree from UCL as a way of marking our collaboration.

In a world that can feel at times increasingly bleak, I leave the sessions with hope

But the greatest privilege is that of being given a chance to play a small role in a project that does such vital work. As we see disharmony, distrust and political disruption on the rise around the world, Holocaust education is more important than ever.

The Centre understands as I now do that human stories are essential if an understanding of the context of Holocaust as a historical event is to be taught and understood. That is how people connect with it.

I understand this through engaging with television audiences, but the Centre brings evidence to this understanding. They weave the stories into extraordinary pedagogy, never making light of the genocide, and yet somehow always keeping it at a human scale.

They are the expert educators. Their human approach is grounded in evidence of what works in the classroom. No one – possibly in the world – has a better understanding of how it is best to teach such a difficult subject. Through their work they reach thousands of teachers and hundreds of thousands of students with their insight.

They do this thanks to government and philanthropic funding. This must continue if their work is to flourish.

Television, of course, has enormous power in ensuring that the story of the Holocaust and its victims lives on, but nothing is more important than education. In a world that can feel at times increasingly bleak, I leave the sessions I do with this wonderful team of expert teachers, alongside wonderful young learners, filled with hope. It is an honour to be part of it.