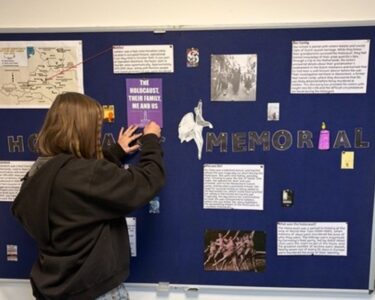

From 1st – 4th May 2015 our Beacon School teachers took part in a study visit of Holocaust sites in Warsaw, Poland. Here two teachers tell us their thoughts, reflections and experiences of the visit.

Julie Haunstetter, History Teacher, Carshalton Boys Sports College

It is incredibly difficult to describe how remarkable our Beacon School Holocaust CDP to Poland was, but it has deepened and extended our knowledge, thinking and pedagogy in a way that no other CDP or learning has ever done, or is ever likely to achieve again.

Paul Salmons and the team from the Centre for Holocaust Education took us on an exceptional four day journey through the streets and buildings of Warsaw and Jadow, a small village in the Polish countryside.

Through the investigation of primary material such as photographs, poems and letters, we endeavoured to get a sense of the vibrancy and scale of pre-war Jewish life, compared to the utter destruction exacted on the Jewish population by the Nazis. We explored an old Jewish tenement, touched the solitary remaining wall of the former ghetto, wandered through the immense, neglected Jewish cemetery and stood in the void of the once Great Synagogue, now a bank. The themes of loss and contrast underscored everywhere we visited, particularly at the site of Umschlagplatz, where deportations to Treblinka commenced. We contemplated the impossible dilemmas faced by some Jews, the memorialisation of those who were murdered and the incredible acts of self-sacrifice and bravery which took place. The most notable of these were the men and women involved in the Ghetto Uprising of 1943, the educator and doctor Korczak, who steadfastly refused to abandon the orphans in his care and the zoo director who hid three hundred Jews over the course of the war, some of whom took sanctuary in the lion enclosure.

Beyond Warsaw, we were warmly welcomed and hosted by some residents of the former Jewish settlement of Jadow, who are seeking to preserve the memory of its former inhabitants. From there we went to Treblinka. At the former extermination camp, we were privileged to be guided by Dr Caroline Sturdy Colls, the only forensic archaeologist to have excavated at this site. Her knowledge and work added a further dimension to our learning, as she discussed her discoveries of mass graves and one of the original gas chambers. To see the artefacts she has unearthed such as a brooch, a comb, a pan – all personal belongings of those who met their fate in that place of infamy, was overwhelmingly touching. This was the complete antithesis to her chilling find of floor tiles from the gas chamber. The beauty and serenity of the site today was also in marked contrast to the heinous crimes perpetrated there.

As ever with The Holocaust, it was impossible to truly grasp its magnitude and horror. However, some basic statistics bought this into sharp focus: Before the war there were four hundred synagogues in Warsaw. Today there is one. Before the war there was a thriving Jewish population of one third of a million people in Warsaw. Today there are six hundred. For me, the most poignant embodiment of this enormous void was captured in the poem, ‘The Monument’, by W. Szlengel, penned whilst confined within the walls of the Ghetto, before his own death in the Uprising. It conveyed the loss experienced by the family of a woman – wife and mother – who was taken from them, one of the eight hundred thousand lives systematically extinguished in Treblinka.

Laura Walton, Head of Religious Education, Stratton Upper School

I’ve been privileged to take over 200 students in the past six years to visit Krakow and Auschwitz. The students have always found it illuminating and, in some cases, genuinely life changing. But I have never been to Warsaw and I was really looking forward to visiting with the UCL Beacon School programme, to see the contrast between the two Polish cities and also between Auschwitz and Treblinka. If you’d have asked me a year ago I would have said that my own subject knowledge was pretty good, but I now realise it doesn’t even begin to make a scratch in the surface of understanding the Holocaust. To have four days of new information was a treat and it also gave me a new found appreciation for what the students go through on a school trip (plus the Schadenfreude of not being in charge – the phrase ‘herding cats’ came to mind occasionally!)

On the first day, the real focus was on understanding the impact that the Holocaust had on the area. The word ‘void’ is often bandied about but I believe that the way Paul Salmons – the Programme Director of UCL’s Centre – took us through activities based on old photographs really helped us to understand it in a way that simply telling us would not have done. Paul did not deliberately mislead us in our task, but he allowed us to discover that all was not as it seemed.

This was also the day when we tried to understand what fragments of the Jewish community remained in Warsaw. Ruth-Anne Lenga conjured up for us what the synagogue would have been like during worship. As she sang out the beautiful Shema, the sense of loss, of what was but is no more, was palpable.

The next day was about exploring the area of the former ghetto and seeing what little was left. It was interesting to see how some of these key sites were marked and we started to get a sense of the scale of the Warsaw Ghetto. There was a rumour that Paul had organised something special for us in the afternoon, but by this point most of us had stopped trusting what he was saying and started just to wait and see what we would discover. Oh, and what a discovery! We turned up at the zoo of all places and heard the most wonderful story about the family who lived there.

The penultimate day was, for me, the hardest. At the former death camp of Trebilnka, we had the absolute privilege to be guided by Dr Caroline Sturdy Colls, a British forensic archaeologist who is investigating the site. Much of this was a revelation to me as although I knew a fair amount about the extermination camp Treblinka II, aside from its existence I knew nothing about the labour camp of Treblinka I. With Caroline pointing out and explaining the methods archaeologists use to survey sites we started to discover the layout and, through that, to understand how the camp was used.

It was, however, discussions at the former extermination camp that made me question myself and my teaching.

I came to Holocaust Education through learning about Janusz Korczak and I have a great appreciation of his life’s work. He has become a figure to me that I have made into a hero – a status that he well deserves. What we actually know about Janusz Korczak is that he accompanied the children from the ghetto orphanage onto the trains in the Umschlagplatz, the deportation centre in Warsaw. Much of what happened next is speculation. As much as I know about the brutality of the extermination camps and about the horrific treatment of all people, but most especially the weakest and most vulnerable people, I had fooled myself into thinking this was different. I wanted to believe the legend that Korczak led the children to as peaceful a death as was possible. That this made his sacrifice worth it. Intellectually of course, I never really believed it, but I never pushed myself to think it through clearly.

The final moments that the children endured confronted me when we arrived at the train platform. It not only made me challenge my own wishful thinking, but also the way we remember people and the way we create heroes. At first I questioned the status of Korczak as a hero and I felt inexplicably let down by him that he would have been forcibly separated from ‘his’ children when they arrived. It was by talking it through with Darius Jackson, another of the Centre’s educators (and one of the most inspiring, left wing, West Bromwich Albion supporting academics I have had the good fortune to spend time with) that I realised Janusz Korczak is not a hero because of the way he died, but because of the way he lived.

When we look at victims of the Holocaust the students first questions are: What happened to them? How did they die? I realise now that the question should be: How did they live?

I need to change the way I teach about people, especially in connection with the Holocaust. So often we focus on the end, but what was important, what should be remembered, is the life that went before. Who wants to be memorialised for one tiny moment of their life, of which they had no control and no influence? When people are in impossible situations, how are we meant to judge or understand the choices they make?

Questions such as these I need to think about and try to answer for my own sake and the sake of my students. Our final day together was a joy for me as we went to the Korzackianum, to find out more about this inspiring man and his life’s work. It felt right and fitting to me that we left Warsaw focusing on his life rather than his death.

The whole experience of working on the Beacon School program has been transformational. This is the most significant CPD I have taken part in, and I am not sure if I will be able to find anything else that matches it.