Meghan McNeeley, an English teacher from Georgia, USA, spent the autumn term attached to the Centre for Holocaust Education whilst enrolled on the Fulbright Distinguished Awards in Teaching Programme.

The Centre’s team supported her whilst she worked on her Capstone Project, the focus being to develop teaching materials that explore women’s experiences of the Holocaust. We hope to share her work with you in the coming months. In the meantime, hear about Meghan’s experience of working with the Centre for Holocaust Education in her own words…

Nearly a year ago, I was honored with a Fulbright Distinguished Teaching Award, an award that has allowed me to live abroad and learn the best educational practices of my host country. American teachers have thirteen countries from which to choose, and since my focus was on Holocaust pedagogy, I selected the UCL Institute of Education, Centre for Holocaust Education as my mentor facility. Out of all the countries and all the institutions I could have chosen, the Centre seemed an obvious (and very prestigious) choice because of its outstanding global reputation and groundbreaking research. As promoted on the Centre’s website, it is “The only Centre dedicated to teaching and learning about the Holocaust that is informed by world class research into teachers’ and students’ needs.” Where else could I ever dream of going?

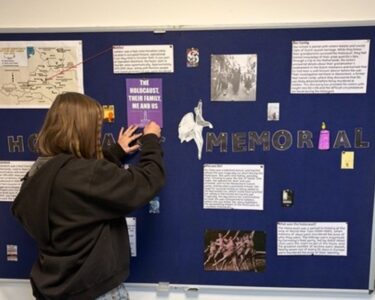

Four months ago I came to the Centre with a Fulbright Capstone Project in mind, “Women and the Holocaust: Rape, Resistance, Rules and Regulations.” My project was intended to generate lessons for the classroom and professional development for educators based on my research into the topic. It was clear from day one that I had a topic that was not only too vast (could I actually do all that in just four months?), but also too challenging and quite possibly insensitive. How could I teach rape to students as young as eleven? Under the guidance and tutelage of my advisor/mentor/guru, Emma O’Brien, lecturer in Holocaust and History Education at the Centre for Holocaust Education, I pared the project down dramatically. Emma encouraged me to consider why I was interested in women and the Holocaust in the first place. From that simple inquiry, it became clear to me that it all went back to Anne Frank.

When I began teaching the Holocaust in 2000, it was The Diary of a Young Girl that was the curricular focus and, quite simply, my inspiration for the next fifteen years of interest, research, and education. Anne Frank was the reason for my interest in women in the Holocaust, and as a result, she became the very nucleus of my work for these four months.

Though Anne Frank drove the focus of my research, I was also here to accomplish another important goal, “to study and observe international best practices in education,” and in working with the Centre, I was certainly able to do just that. I observed and participated in professional development opportunities for Holocaust educators, both pre-service and in-service, in several parts of England. I was more than impressed with all the teacher education programmes the Centre maintains: the Initial Teacher Education programme, which works with pre-service teachers, helping them to teach the Holocaust respectfully and appropriately; the Continuing Professional Development sessions (CPD) for more seasoned teachers that encourage secondary school educators to better develop their subject knowledge and to guide their pedagogy of the Holocaust; and the Beacon School Programme which develops Holocaust education leaders in communities all over England. These programmes were inspirations for what Holocaust education could be in my home state of Georgia, and models for my future professional development courses.

Work on my project wasn’t always straightforward or focused. It was a struggle and a challenge, but I always had the support of the Centre’s team of educators. Darius Jackson spent several hours with me sharing his work on Anne Frank and her legacy. Andy Pearce and Ruth-Anne Lenga invited me to observe their professional development sessions. Paul Salmons allowed me to participate in the Beacon School Residential Programme, a five-day course where I was able to meet and work with Holocaust educators from across England. Rebecca Hale shared aspects of the Centre’s research with me. And Emma O’Brien was there for every question, concern, conundrum, and quandary that I faced – and there were plenty! Because of Emma, and the others, I was able to create five lessons on women and the Holocaust that are supplemental to a study of The Diary of a Young Girl, as well as plans and materials for teachers’ professional development when I return to Georgia in 2015.